Function Color Theory

In 2015, renowned programmer Bob Nystrom published an article "What Color is Your Function" on his blog, which was thought-provoking and sparked intense discussion within the industry. Six years have passed, and it remains evergreen in programming language forums.

Original article: What Color is Your Function? I must warn you that the original is very long, requires high programming fundamentals, and is full of English puns. I strongly recommend reading my "vernacular analysis" first, then savoring the subtleties of the original.

Disclaimer

This article is not a translation of the original. I've added many code examples to demonstrate the author's ideas. In the latter half of the article, I've added some content regarding the state of languages in 2021. Most interestingly, this article wonderfully intersects with my series "Deep Dive into Memory Management." In the final "Call Stack vs Event Loop" section, I've departed from the author's manuscript to add some of my own thoughts.

A New Language

To avoid offending specific language enthusiast groups, the author invented a new language. Don't panic - it reads like pseudocode: parentheses, semicolons, and keywords like if and while.

function thisIsAFunction() {

return "It's Awesome!";

}

This new language naturally supports modern language features like higher-order functions. Higher-order functions allow functions as parameters. For example, in the following code, predicate is a lower-order function returning a boolean value, and the higher-order function filter accepts it as a parameter.

// predicate is a lower-order function passed as parameter to filter.

function filter(arr, predicate) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (predicate(arr[i])) result.push(arr[i]);

}

return result;

}

// For example, we use positive function to check if a value is positive.

let positive = x => x > 0;

// Then we pass positive to filter

filter([-1, 0, 1], positive);

// The final result is [1, ]

Friends, higher-order functions are so satisfying to write. Over time, we'll stuff our programs full of higher-order functions.

// For example, I start using higher-order functions to write testing frameworks

describe("An Apple", function () {

it("ain't no orange", function () {

expect("Apple").not.toBe("Orange");

});

});

// Or, I start using higher-order functions to write compilers

tokens.match(TOKEN.LEFT_BRACKET, function (token) {

// Parse array sequence

tokens.consume(TOKEN.RIGHT_BRACKET);

});

After going overboard, I start writing functions that return functions (wrappers), some chained calls. I love iterator().filter().map().collect() - this way my code has none of those rookie for and while loops.

Function Colors

That was just the tutorial village. This new language looks no different from JavaScript/Python. We're about to encounter the first Boss. Now the rule is: Every function has a color - either red or blue. Whether named functions or anonymous functions must follow this rule.

Anonymous functions... I heard you prefer calling them "closures" or "lambdas".

Now we can't use function to define functions anymore, only red function and blue function keywords to explicitly specify function colors.

blue function doSometingBlue() {

// This is a blue function

}

red function doSomethingRed() {

// This is a red function

}

There are no colorless functions! If you want to define a function, you must choose a color!

The author ruthlessly added four more annoying rules:

-

When calling functions, you must also add the corresponding color after parentheses.

doSomethingBlue()blue; // Call blue function doSomethingRed()red; // Call red function -

Red functions can only be called within red functions; blue functions cannot call red functions.

// This is a red function red function doSomethingRed() { doSomethingBlue()blue; // Can call blue functions doSomeRedThing()red; // Can also call red functions } // This is a blue function blue function doSomethingBlue() { doSomethingBlue()blue; // Can only call blue functions } -

Red functions are expensive. Each red function call costs programmers $100 in tax.

-

Some core library functions (like network requests) are red.

Functional Programming's Fault

It must be because I wrote too many higher-order functions that heaven is tormenting me this way. Now my code won't compile at all: blue and red are chaotically mixed in the code, and the compiler keeps reporting errors. If I had obediently written for and while loops, I wouldn't have this headache now.

If all functions were the same color, that would be manageable. Make them all red? I don't want to waste thousands of dollars (see rule 3). How about making them all blue? Programming isn't hard: When defining new functions, if we're sure we only need to call blue functions, define as blue; otherwise define as red. As long as we don't write higher-order functions, we don't need to worry about "polymorphism."

Okay, chant the mantra: blue first, blue first, blue first, use red only when absolutely necessary.

But wait, is this right? Suppose we write a core feature (e.g., sending data to server) that will be reused countless times throughout the project. I naturally want it to be blue. However, because it calls red core library functions, it must be a red function.

Great, now only red functions can use this core feature. If my colleague is writing a blue function blue function foo() and suddenly needs to call this core feature, what should they do?

- Change the blue function

blue function foo()to redred function foo(). Change all call statements fromfoo()blue;tofoo()red; - Change all blue functions calling

foo()redto red functions. - Change all blue functions calling blue functions that call

foo()redto red functions. - Change all functions calling functions calling functions...

Do you see? Red is contagious. A single spark can start a prairie fire - using red is inevitable.

The Color Metaphor

Alright, let's stop riddling. Color here is just a metaphor. Now for the reveal:

Red functions are async functions.

If you're familiar with JavaScript programming, you'll realize: every time you pass return values through a "callback function," you create a red function.

// Look familiar?

function SendMsg(url, params, cb) {

http.post(url, params, response => {

// 👈 Callback hell

let reply = response.data.msg;

cb(reply);

});

}

- Sync functions return a value. Async functions have no return value but call a "callback function."

- Calling sync functions uses

let rtval = foo(a, b), calling async functions usesfoo(a, b, (x)=> {this.rtval = x;}) - Sync functions cannot call async functions because async functions have no return value.

- Async functions are very hard to handle - their error catching and control flow statements are all different from sync functions.

- All of JS is an EventLoop! Node.js itself is a giant async function!

What is callback hell? Maybe it's writing many brackets, indenting layer by layer until exceeding screen display range... The essence of callback hell is too many red functions in code. Nowadays there are tens of thousands of third-party libraries that are red (async). This is the current state.

Promise and Await

Many programming languages introduced Promise and Async/Await syntax sugar to alleviate async problems. This syntax sugar undoubtedly solves some pain points in using async functions.

async function SendMsg(url, params) {

let resp = await http.post(url, params);

return resp.data.msg;

}

async function invoker() {

let reply = await SendMsg(url, params);

// Directly expand cb() function here

}

But the author believes that whether Promise or Async/Await, they're just prettier syntax sugar added to the language. Essentially, our functions still have two colors - you still can't call async functions within sync functions. Creating red functions might be easier, but blue functions still can't call red functions.

So once I start writing higher-order functions or reusing code, I'm back to the exact same predicament as before. Here's an example. Now there's an array storing usernames. I want to send these usernames to the server in sequence to get their detailed information. Let's try writing it with higher-order functions~

// We have an async/await async function

async function getInfoFromServer(user);

// We also have a callback version

function getInfoFromServerCb(user, cb);

// This is our main function

function main() {

let users = ["whexy", "macromogic", "mstmoonshine", "nekodaemon"];

print(getUserInfo(users));

}

function getUserInfo(users) {

let infoList = users.iter().map( (user) => {

let info = await getInfoFromServer(user);

return info;

// ❌ Can't write this way, map is not an async function!

getInfoFromServerCb(user, (info) => {

resultList.push(info);

// ❌ Can't write this way, resultList is still empty when returned!

})

// Ahhh... no matter how I write it's wrong

})

}

You see, our higher-order function map() is a typical blue function, while getInfoFromServer is a red function. Even with syntax sugar, this requirement is still hard to fulfill.

Real-World Language Colors

So languages like JavaScript, Dart, C#, Python, etc., mostly face function color problems.

From here onward, the following discussion differs from the original article.

Which languages don't have color problems then? Java, right? Java indeed used to be a language without color problems. Too bad Java is actively introducing Futures and Async I/O. In the near future, Java programmers will also face color choices.

Languages truly without color problems are: Go, Lua, Ruby. They all share a common feature - multithreading. More precisely, they all have multiple call stacks that can context-switch. The threads here don't necessarily need to rely on the operating system - Go's GoRoutines, Lua's coroutines, and Ruby's fibers can all avoid color problems.

More languages belong to an intermediate category: they can avoid color problems. For example, Swift, Rust, C++. The prerequisite is not using the event loop model.

Call Stack vs Event Loop

I think I've finally reached the most essential issue. When an operation completes, how do you continue from where you left off?

foo();

bar();

let file = readLargeFile(); // Very heavy IO operation

// We leave from here to do other things

// IO ends, we return here to continue working

let size = file.length();

We performed some IO operations, using the operating system's underlying async API for performance. When the OS is busy with IO operations, the program must switch to handle the next task, otherwise the interface will "freeze." Once the OS completes the task, we need to restore to where we originally left off.

Call Stack

The most common approach is to get along well with the operating system. It can help us record where we left off, then "restore the scene" after work is done to continue execution. This is the call stack recording method.

If we don't like the OS's clunky context switching, we can also let the language runtime act as the recorder. For example, GoRoutine's runtime can manage its own "threads," also called "user-space threads," "green threads," "fibers," etc. These complex names actually still represent the threading model behind the scenes, fundamentally no different from call stack recording.

Event Loop

But these colored programming languages (especially interpreted languages) don't like the concept of threads. For example, JavaScript, as a language running on web pages, never considered multithreading in its initial design. But we happen to need to handle other affairs while performing IO operations, which introduces "async."

Functional programming theory introduces the concept of "closures." Closures are anonymous functions that can capture context.

fn main() {

let x = 4;

let equal_to_x = |z| z == x;

let y = 4;

assert!(equal_to_x(y));

}

Capturing context... capture... context... Isn't this another way to record where we left off? Many runtimes generate structs to store closure environment information. Adding closures to the event loop is another way to "restore the scene."

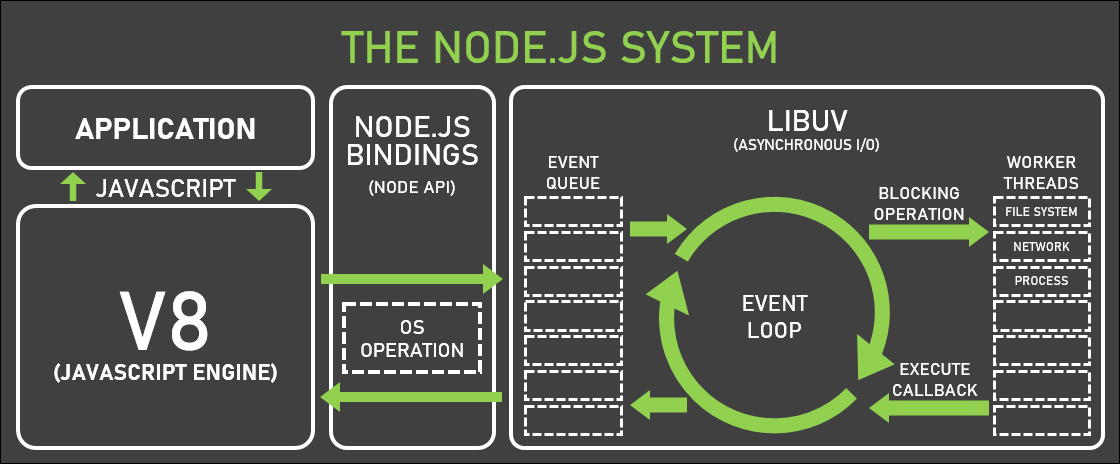

Node.js Event Loop Model

The Event Loop is essentially a giant while true loop, a mechanism that continuously polls tasks. The program is abstracted as a collection of "events" (also called tasks), added to queues and completed one by one. Event execution can have prerequisites (e.g., event C must be executed after completing event A), forming event dependency relationships - equivalent to function call chains. Remember the callback closures we wrote earlier? They're new events added to the queue during execution.

Imagine we want to read several files. The main function calls the OS's async read API several times and adds corresponding callback events to the Loop. The event loop continuously searches for executable tasks in the event list, like handling user clicks and page scrolling. When a file finishes loading, its corresponding callback event is activated in the queue. In the next loop iteration, this callback event can be executed promptly.

Wow, reaching here is truly a bonus. I accidentally introduced the principle of coroutines: it's actually the event loop model.

You might wonder: what do these so-called "events" look like to the operating system? How do they exist in memory? Consistent with closure handling principles, these "events" are data structures stored on the heap. This is a special memory management model - if you're interested, you can follow my "Deep Dive into Memory Management" series.

Event loops sound cool, but as repeatedly pointed out earlier - they're inevitably affected by the red-blue function color problem.

Summary

In this article, I first introduced function color theory. Original article: What Color is Your Function?. If your English is up to par, I strongly recommend savoring the original. Some discussions in the original that I didn't cover in this article are all breathtaking.

Finally, we touched on three async models: OS threading model, "user-space threading" model, and event loop model. Readers who persevered to read this far will surely understand: there's no absolutely elegant model.

- Using OS threads is the simplest programming paradigm. The OS can help record and restore context. The prerequisite is language support. (Isn't it ridiculous that so many "programming languages" don't fully support or don't support at all?)

- Using user-space threads like GoRoutines. This is the model the original author most appreciates - reducing context switching overhead while maintaining function color purity. Combining language aesthetics with practical benefits. But I must pour cold water: when project complexity exceeds a threshold, thread scheduling = concurrency bugs. In this model, we have to use various synchronization primitives to ensure data flow consistency. The "user-space threading" model also increases the difficulty of detecting concurrency errors. (See blog Alligator in Vest)

- Using the event loop model. Of course, you'll face function color dilemmas, but well-trained programmers can overcome this drawback. Another drawback: event loops have additional runtime overhead. The advantage of the event loop model is no preemptive scheduling, greatly reducing concurrency bug existence. Of course, one event "freezing" will block the entire program's execution. So the famous Kotlin backend framework Vert.x emphasizes "Don't block me." When writing languages using the event loop model, always be careful not to write blocking code. (See blog SUSTeam: Ultimate Gaming Platform)

If you like this blog or want to get notifications immediately, you can subscribe to updates via RSS. Also welcome to follow my GitHub and Twitter accounts - I'll share more high-quality content about computer systems security. If you have any questions or suggestions about this article, please leave comments below. See you~

© LICENSED UNDER CC BY-NC-SA 4.0