Annual Hit Piece: Fuzzing Top Conference Paper Debunking Report

Author's Disclaimer

This article is mainly a summary of the fuzz-evaluator report content and does not represent my personal views. For the original text, please visit SoK: Prudent Evaluation Practices for Fuzzing. I am not responsible for any interpretation errors that may arise beyond the article. The data and viewpoints in the article are for reference only and do not constitute any advice or opinions.

Fuzzing refers to "fuzz testing" in the software security field, a brute-force vulnerability discovery testing method. Fuzz testing randomly generates some inputs, then observes program behavior. If the program exhibits anomalies on certain inputs, those inputs might have discovered a "vulnerability." Although the industry has proposed "whitebox" and "greybox" testing methods to increase controllability, randomness remains the core characteristic of fuzz testing.

At top conferences, the number of papers on fuzz testing is growing year by year. However, due to fuzzing's high randomness, large resource consumption, and long runtime, reviewers find it difficult to confirm the effectiveness of paper methods in a short time. Therefore, there are often papers of questionable quality that get accepted (even win awards). Many teams attempt to verify paper effectiveness by reproducing experimental data from papers.

Of course, these reproductions can also spark controversy. For example, in December 2023, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Assistant Professor Dongdong She blasted on Twitter the reproduction results of his 2019 Oakland conference paper NEUZZ by German CISPA team led by Professor Andreas Zeller.

Dongdong She questioning reproduction results on Twitter

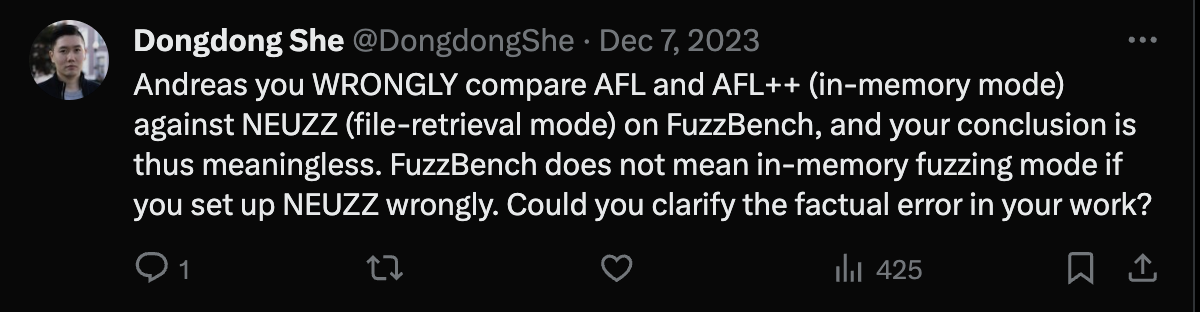

The two went back and forth on Twitter for several pages. Others also stood with Professor Andreas Zeller, together questioning Dongdong She's paper as "complete fraud."

Cornelius's Twitter screenshot

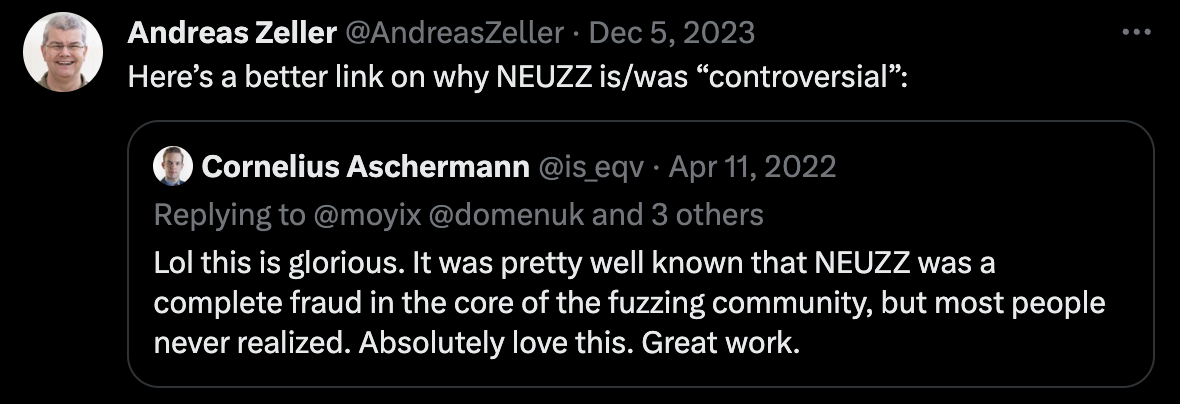

Finally, Professor Andreas Zeller ended the dispute with passive-aggressive blessings.

Professor Andreas Zeller's response to Dongdong She on Twitter

Gods fight, mortals watch the show. As a fuzzing newbie just starting out, I'm not qualified to participate in this dispute. But I still want to know, how many fuzzing papers are actually "fraud"? And how high is the degree of "fraud" in these papers?

Background Introduction

CISPA

The German CISPA team mentioned above has relatively high reputation and influence in the fuzzing field. They also maintain good relationships with Google's fuzzing team, enabling them to obtain large amounts of real and reliable test data.

Google & Fuzzing

Google has rich experience and resources in the fuzzing field. Their OSS-Fuzz project is the industry-recognized fuzzing platform and benchmark in the fuzzing field. Their researchers also participate in developing or maintaining famous fuzzing tools like AFL, honggfuzz, libAFL, syzkaller, as well as test suites like Fuzzing Test Suite (FTS) and FuzzBench.

Recently, we noticed a GitHub account named fuzz-evaluator that has been updating reproduction results of fuzzing papers. These reproduction results are published as GitHub repositories, including reproduction code, data, experimental environments, etc. We're not surprised to find that these reproduction results often differ from the original papers' experimental results. Privately, we all call it the "Fuzzing Police."

Until a few days ago, we discovered that the CISPA team published a paper at S&P 2024 titled SoK: Prudent Evaluation Practices for Fuzzing. This paper summarizes their survey results of more than 150 top conference fuzzing papers over the past six years and analyzes these papers' experimental data. It turns out the fuzz-evaluator account was registered by their team.

fuzz-evaluator's Survey Results

Reproducibility

In the article, they first surveyed reproducibility. The reproduction workload of 150 top conference papers is very large, so they chose to focus on four indicators: ①whether artifacts were submitted, ②whether code was open-sourced, ③whether data was made public, and ④whether reproduction badges were obtained. Among them:

- 74% of papers chose to open-source their proposed fuzzing tools;

- 11% of papers chose to make test data public. Among these papers that chose to make data public, 64% decided to make data public because they didn't open-source;

- 36% of papers didn't submit artifacts. Another 37% of papers submitted artifacts but didn't receive any badges. Only 26% of papers submitted artifacts and received at least one badge.

Of course, not open-sourcing or not submitting artifacts doesn't necessarily mean there are problems with the papers. After all, open-sourcing and submitting artifacts both require additional work. But these indicators can serve as reference.

Test Targets (Programs Being Fuzzed)

When evaluating fuzzing tools, we need to find some programs to be fuzzed as targets. For example, it's better to choose real programs as test targets rather than artificially constructed programs. Also, it's better to choose widely-used programs as test targets rather than outdated programs. Among these 150 papers, they found:

- On average, each paper only tested 9 targets;

- Among all test targets, 76% of targets were only tested by one paper. This means most test target results weren't verified in other papers;

- 61% of papers don't use public test suites but chose test targets themselves.

Test suites are collections of public test cases, such as FuzzBench, FTS, etc. These test suites are maintained by industry experts and can guarantee test case quality. Choosing test targets yourself might result in selecting outdated targets or targets without representativeness.

Even so, when choosing test suites, timeliness must also be considered. Among papers that used public test suites:

- 17% of papers used LAVA-M, 5% of papers used CGC. These are two outdated test suites;

- 10% used FuzzBench, 8% used FTS, 4% used Magma, 1% used UniBench. These test suites are relatively new and industry-recognized.

Comparison Baselines

Generally, when testing new fuzzing tools, we choose some existing fuzzing tools as comparison baselines. These baselines are generally industry-recognized fuzzing tools, such as AFL, AFL++, libFuzzer, etc. Among these 150 papers, they found:

- 35% of papers compared with AFL;

- 6% of papers compared with AFL++;

- 5% of papers compared with libFuzzer;

- 23% of papers didn't compare with SOTA.

Interestingly, all the popular comparison baselines above are not fuzzing tools proposed by academia. Does this mean the gap between academic and industry fuzzing tools is still quite large?

Of course, they also summarized the top three most compared academic fuzzing tools. They are: FairFuzz (particularly bad), Qsym (particularly slow), MOpt (decent results).

Experimental Environment

Maintaining consistency and fairness in experimental environments is very important. Among these 150 papers, they found:

- 15% of papers didn't describe experimental environments;

- 5% of papers used biased resource configurations;

- 5% of papers used biased initial seeds.

We were surprised reading this. Because using biased resource configurations is easily discoverable from paper text. Does this mean reviewers didn't carefully review the papers? If experimental environments themselves are biased, then paper experimental results are unreliable. These papers combined also account for a quarter of top conference papers.

Data Testing

Finally, summarization and analysis of experimental data is very important. Among these 150 papers, they found:

- 63% of papers didn't use statistical tools to analyze data;

- 15% of papers repeated experiments fewer than 5 times;

- 73% of papers didn't provide confidence intervals or standard deviations.

As we said at the beginning, fuzzing is a testing method with strong randomness. Therefore, statistical analysis of experimental data is very important. Only this way can we ensure experimental result reliability. We understand that some authors might not be familiar with statistical tools, but repeating experiments fewer than 5 times is unacceptable.

Common Experimental Errors Summarized by fuzz-evaluator

At the end of this SoK, the fuzz-evaluator team gave examples, established typical cases, and criticized some papers, summarizing common experimental errors. Some papers they mentioned are from authors I'm quite familiar with, even have decent relationships with. But we must always uphold justice, not show favoritism, eliminate relatives for the greater good.

- MemLock (ICSE'20, artifacts reusable) used unique crashes as metrics, which don't correspond to actual bug discovery numbers. "Unique crashes" is a deduplication strategy for saving seeds that cause program crashes, but doesn't mean seeds are completely non-duplicate;

- SoFi (CCS'21) found "vulnerabilities" and submitted them to original code authors, but authors rejected them all. That is, these "vulnerabilities" weren't real vulnerabilities;

Actually, using vulnerability discovery numbers, especially new CVE numbers as evaluation metrics is problematic itself. Who knows if these vulnerabilities were discovered using fuzzing? After all, fuzzing is a highly random testing method. These vulnerabilities might have been discovered by other testing methods or other people. Maybe they can be found this time, but not next time. So we should use denser, more objective metrics like code coverage to evaluate fuzzing tools.

Even using code coverage, some papers used unfair or irreproducible comparison methods. For example:

- DARWIN (NDSS'23 distinguished paper) didn't provide baselines during testing, actually only 1.73% higher than AFL. It claimed to lead on 15 targets, but actually only on 4;

- FUZZJIT (USENIX'23) claimed 33% higher code coverage than SOTA, actually 12% lower;

- EcoFuzz (USENIX'20) used "path numbers" as metrics, actual code coverage (branch coverage) was lower than all comparison baselines in the paper;

- PolyFuzz (USENIX'23) used different initial seeds for comparison, gaining 273% initial advantage;

- FishFuzz (USENIX'23) used unfair instrumentation when measuring coverage, its claimed 8.44% improvement was actually only 1.69%.

Conclusion

Regarding the fuzz-evaluator report, we have many feelings. First, we're not surprised by their conclusions at all. Anyone who's a researcher in the fuzzing field has more or less tried reproducing others' papers. Such high irreproducibility rates are also our personal experience. There's no shortage of researchers broadcasting this conclusion in recent years, but fuzzing papers continue to be accepted constantly. Improvements of 10%, 20% at will. We also know the authenticity of these improvements in our hearts.

Launching satellites, boasting big - these seem to have become the norm in the fuzzing field. Now, some truly valuable research is buried under these gimmicks. We need more people to stand up and criticize irresponsible research. We need more people to stand up and affirm valuable research. Anyone can tell stories, anyone can make principles sound lofty, anyone can list a bunch of formulas, but can you complete all targets in benchmarks? Can you avoid cherry-picking cases? Can you improve branch coverage by 3% on average?

Finally, rather than doing experiments behind closed doors, we need more open and transparent arbitration mechanisms. For example, Google's FuzzBench project is a great example. Besides a very good test set, it also provides an open and fair testing environment. Free Google cloud machines, write a few lines of Dockerfile and you can run experiments on it (no need to open-source, just provide binaries in Docker). I suggest all published fuzzing papers should be publicly tested on FuzzBench, lest industry looks down on us. We can at least avoid some irresponsible researchers fooling reviewers with little tricks.

For another example, participating in open fuzzing competitions is also a great method. Such as the SBFT Fuzzing Competition that's been held for the past two years. The 2023 winner was Hastefuzz, which just turned off the sanitizer and left everyone in the dust - doesn't this embarrass those papers claiming 20% improvements? The 2024 winner was BandFuzz, not open-sourced, we don't know who wrote it temporarily, nor do we know if they'll also boast in papers. But at least their experimental results are open and reproducible.

Doing fuzz, say it's simple and it's simple, say it's hard and it's hard. Fuzzing doesn't require much deep mathematical theory, nor detailed engineering understanding of systems. This lowers the field's barriers, anyone can come and have a say. However, how to do valuable research in this field while standing out among a group of mediocre people is a question worth thinking about.

© LICENSED UNDER CC BY-NC-SA 4.0